Move Over, Hollywood. The French Invented Film Noir and They Do It Exceptionally Well.

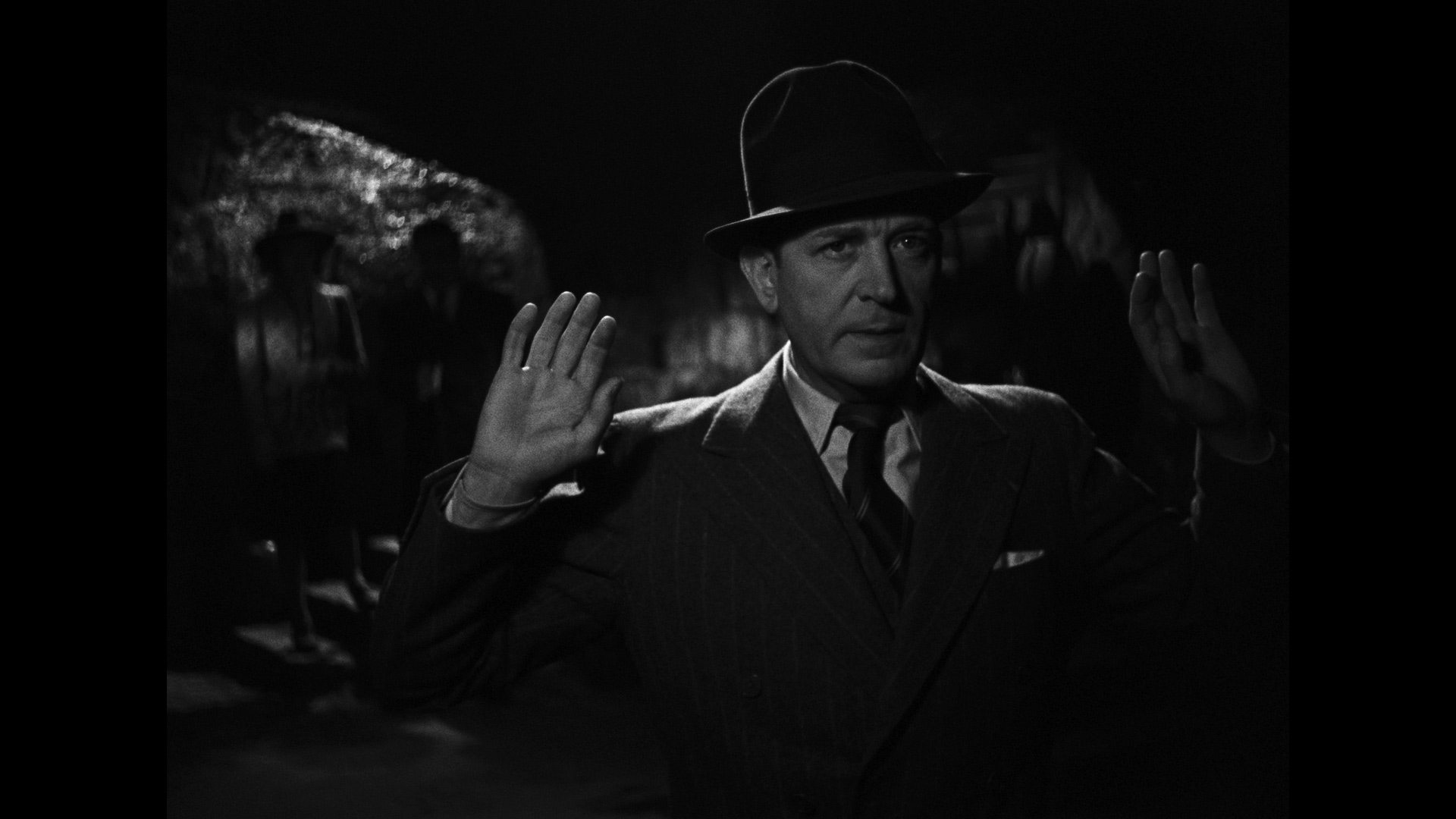

When you think of film noir, chances are iconic actors like Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall come to mind. Perhaps classic American noir titles like The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, or Double Indemnity. But, as the name noir suggests, what you associate with the genre might not be the origins of it. In fact, film noir is largely rooted in French cinema, which not only heavily influenced American noir but continued to produce important contributions to the genre long after Bogart put on a fedora and trench coat.

In the 1930s, a film movement called poetic realism emerged in France that sought to capture the hardships of human existence in a lyrical, almost romantic style. Influenced by German Expressionism, the movement saw characters struggling with poverty, disillusionment, and other adversities depicted in atmospheric black and white, accented with chiaroscuro lighting, and framed elegantly in postcard-worthy tableaus. This created an irresistible tension between the gritty storytelling and the beautifully melancholic look and feel. If this sounds eerily similar to noir, it’s not a coincidence.

When film noir rose to prominence in the mid-1940s, the genre absorbed the distinct look and feel of French poetic realism but added its own signature tropes and motifs: the hard-boiled detective, the femme fatale, the gangsters, the corrupt underbelly of society, and of course, the existential dread of being trapped by your own fate. In 1946, French film critic Nino Frank officially coined the term “film noir,” and although he was referring to Hollywood films, France continued to be a mecca for the genre throughout the ‘40s and well into the ‘50s and ‘60s.

In celebration of Noirvember, we’re spotlighting some of the most essential French noir films ever made. Stream them all on Kino Film Collection this month.

Un Flic (1972)

Un Flic is the final film from Jean-Pierre Melville, who was widely considered a pioneer of independent filmmaking and the godfather of the French New Wave. Melville’s work influenced the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol. But what influenced Melville? “I make gangster films, inspired by the gangster novels,” he told Sight & Sound magazine in 1968, “Even though I like the American films noirs better than anything.” Featuring Alain Delon, who starred in three of Melville’s films, Un Flic is a perfect last entry to Melville’s illustrious career. The story follows a disillusioned detective named Commissaire Edouard Coleman (Delon) who falls for the mysterious and evasive Cathy (Catherine Deneuve). Things get complicated when Edouard discovers that his friend Simon (Richard Crenna), who is also Cathy’s boyfriend, is a criminal mastermind planning a major drug heist. Set against a neon-lit Paris, inside smoky nightclubs, and along desolate empty beaches, Un Flic is a prime example of France’s enduring contribution to film noir long after Hollywood’s golden era.

Witness in the City (1959)

From director Édouard Molinaro, Witness in the City has everything a noir fan craves: murder, vengeance, high-speed car chases, all steeped in high-contrast black and white. Based on the novel by the French author duo Boileau-Narcejac, who wrote several works that were adapted into film (including Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo), Molinaro’s adaptation opens with a vengeful widower’s meticulously planned murder of his wife’s killer. As Ancellin (Lino Ventura) leaves the victim’s mansion, his tidy execution is unraveled when a taxi driver bumps into him and witnesses him leaving the scene of the crime. What ensues is a tense cat-and-mouse game, heightened with the help of legendary cinematographer Henri Decaë, who worked with Melville on Bob Le Flambeur and Le Samouraï. With minimal dialogue, skillful camera techniques (jump cuts, distorted focus, close-ups), a captivating jazz score, and the city of Paris as a central character, Witness in the City is a must-view in the French noir canon.

Speaking of Murder (1957)

Gilles Grangier’s Speaking of Murder stars Jean Gabin, who has been equated to France itself. In the 1930s, the actor rose to prominence playing tragic figures from the depths of society—thieves, murderers, army deserters—and cemented his status first as an icon of poetic realism and then later as France’s go-to noir anti-hero. In Speaking of Murder, Gabin plays Louis, a hardened gang leader, who gets involved in a deadly police shooting. Cracks form in the gang as the ruthless Pepito (played by Lino Ventura from Witness in the City) starts to suspect Louis’s kind-hearted brother Pierre of being a snitch. One of the most memorable scenes in the film sees Louis charming Pierre’s girlfriend Hélène for an extended period of time before he suddenly turns on her and demands she stay away from his brother. In a 1959 review of the film, The New York Times describes Gabin’s performance of having a “deceptive, dead-pan casualness, like a relaxed aging cobra.” What better encapsulation of a man who’s spent 20 years playing tragic anti-heroes?

Alphaville (1965)

Before Blade Runner and Dark City, there was Alphaville, which was considered to be the first true noir-scifi hybrid. In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 film, the predominant noir strand is its protagonist Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine), who embodies the same cynicism, gruffness, and machismo—occasionally cut with witty one-liners—that Humphrey Bogart’s Philip Marlowe does in The Big Sleep. But the rest of the film reflects a whole new set of anxieties, an evolution of sorts from post-war unease to full-blown fear of human extinction at the hands of technology, which was at the time burgeoning at inconceivable rates. In fact, the antagonist in Alphaville is not human at all, but a sentient supercomputer dictator called the Alpha 60, which has outlawed free thought, poetry, love, and other emotions. Lemmy has been sent to destroy the Alpha 60 and its creator, Professor Von Braun, but falls in love with Professor Von Braun’s daughter Natacha (Anna Karina) in the process. For a film made nearly 60 years ago, its themes involving sentient technology obliterating any trace of humanity feels more pressing than ever.

Back to the Wall (1958)

Some of the best thrillers open with what feels like a pivotal climactic scene and the rest of the movie unpacks how we got there. Édouard Molinaro’s (Witness in the City) Back to the Wall opens with a mysterious man in a trench coat and fedora stealthily entering an apartment, packing up a suitcase, and carting off a dead body in a rug. He then drives it to a factory and buries it under a fresh layer of cement. Who is the body? What did he do to deserve this ill fate? The remainder of the film is told through flashbacks, through which we learn that the mystery man is Jacques (Gérard Oury), a wealthy industrialist whose wife Gloria (played by the inimitable Jeanne Moreau) is having an affair with a young actor, Yves (Philippe Nicaud), who we recognize as the corpse in the opening scene. Consumed by jealous rage, Jacques begins anonymously blackmailing Gloria and torments her into desperation. But how does that connect with Yves’ death? Like with any good noir, nothing is as it seems in Back to the Wall.

Picpus (1943)

Richard Pottier’s Picpus is the first of three film adaptations of Georges Simenon’s work following the pipe-smoking detective Jules Maigret. In all three, Maigret is played by Albert Préjean, who lends the detective a casual jocular attitude. Picpus is centered around a string of murders that take place near the metro station Picpus and Maigret’s twisty investigation that follows. While moving into her new Paris apartment, Madame Dumont discovers a dead body in her wardrobe, and soon more bodies pile up. A blind man, a clairvoyant, a doctor, a real estate agent—what could their connection be? Though not nearly as cynical and bleak as most noir films, Picpus still has the markings of a noir with its liberal use of shadows, its mounting sense of dread, and of course its hard-boiled detective, who may not be as gruff as Marlowe but just as formidable.

Cécile Is Dead! (1944)

Cécile Is Dead! is the second film adaptation of Simenon’s Maigret novels, also starring Albert Préjean, but this time directed by Maurice Tourneur. The story begins with the titular Cécile, a somewhat frumpy young woman, turning up to Maigret’s office repeatedly, complaining of a home intruder. But without any actual theft (the culprit moves her things around, but never steals anything), there’s not much Maigret and his colleagues can do. Though his colleagues sneer at her, something in Maigret’s gut tells him to look into the matter… but it’s too late. Both Cécile and her aunt are found dead, strangled in their shared home. Maigret sets out to solve their murders, but true to a Simenon story, the case is anything but straightforward.

Bob Le Flambeur (1956)

Another one of Jean-Pierre Melville’s finest works, Bob Le Flambeur is one of the most quintessential bank heist films in history. Roger Duchesne plays the titular Bob, who is as cool as any gambling addict can be. He’s well-respected by everyone in his circle, including Police Commissioner Ledru, whose life he once saved. For a guy who was once a convicted bank robber, that kind of friendship says a lot about his character. When Bob hears that the casino he frequents will be getting an influx of cash (800 million francs to be exact), he devises a plan to rob the safe and assembles the perfect team. But news of this nature is bound to get around with the company he keeps, and eventually his old buddy Ledru catches wind. Will his losing streak continue or will he finally make the right bet? In Melville’s world, the tides of luck change quickly and can swallow you whole—a very noir notion.

Port of Shadows (1938)

Marcel Carné’s Port of Shadows has been hailed as a quintessential example of poetic realism and a thematic precursor of film noir. But with its gray palette, story of romance and revenge, and the persistent sense that fate is going to catch up to its characters, some have placed the film squarely in the latter category. Featuring a career-defining performance by Jean Gabin, Port of Shadows follows presumed army deserter Jean (Gabin) looking to make his way to the port city of Le Havre to start over. He finds himself at a bar on the edge of town, clearly a watering hole for the city’s lost souls, where he meets Nelly, a young woman also escaping a painful past. Soon he falls in love with Nelly and becomes entangled in a group of people who offer him anything but a clean slate. Ultimately, Jean’s fate does indeed catch up to him and the port itself becomes an allegory for second chances that, when enshrouded in fog and desperation, can be easy to miss.