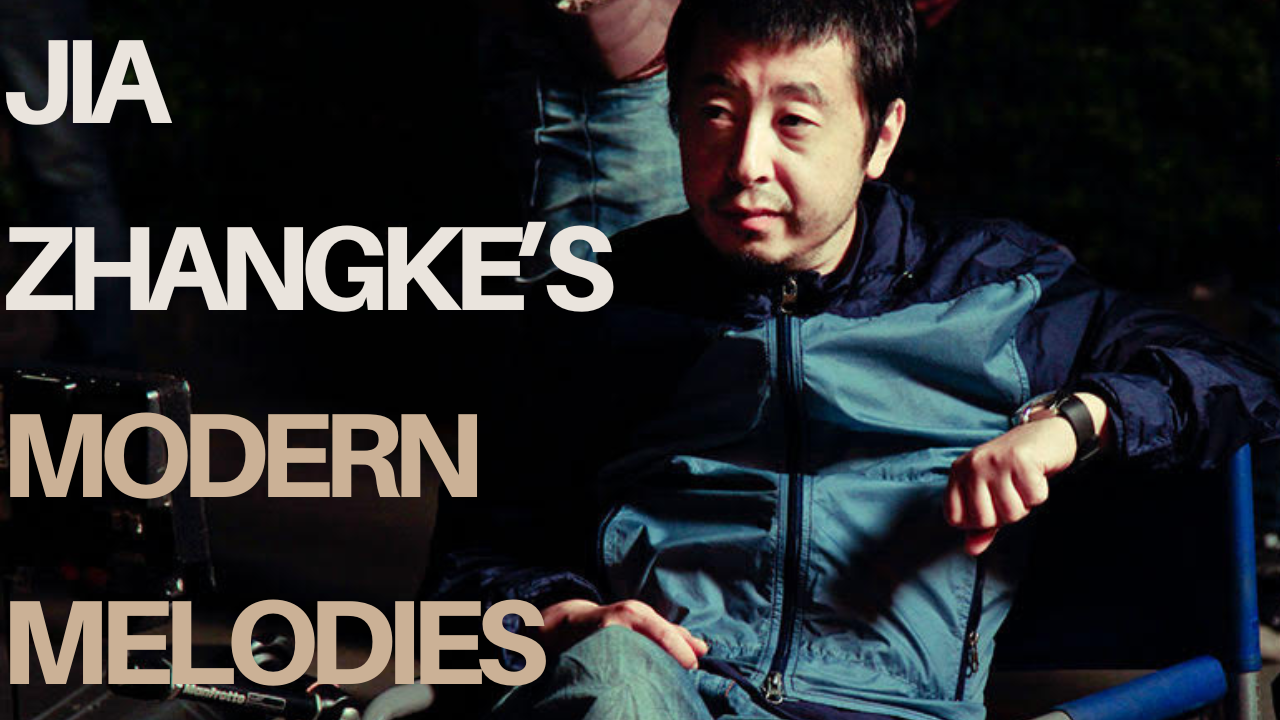

Spotlight On: Chinese Auteur Jia Zhangke

At Kino Film Collection, we celebrate filmmakers who leave an indelible mark on their craft. There’s no better example of that than Jia Zhangke. As part of our August Auteurs series, Aurelia Dochnal examines the political undertones of Jia's work, his focus on the marginalized corners of China, and the enduring reverberations of his message.

Jia Zhangke is not an overtly political filmmaker, yet politics is everywhere in his work. A leading Chinese filmmaker, Jia has spent the last 30 years memorializing the bewilderments of modernity. From a young pickpocket adapting to urban change to an itinerant woman on the run from the law, Jia’s protagonists are slightly out of sync with the demands of their time. For me, it’s his careful attention to ambient sound that resonates loudest. Jia’s modern melodies have taught me to be a more alert political subject, paying attention to manifestations of power in daily life.

In contrast to the heavily polished soundtracks of other Chinese movies, Jia layers his movies with the sounds of quotidian city life. We hear government announcements play on the city center’s public loudspeaker. A young woman clandestinely intercepts a Taiwanese love song through the radio, dancing in a room alone. Teenagers listen to weather reports from Ulaan-Bator, imagining an escape from their hometown. Sound is not only an atmospheric addition in Jia’s cinematic universe: it is the primary medium of his sociopolitical observation.

Recently, in a bagel shop in New York, I heard a Department of Homeland Security radio broadcast urging immigrants to self-deport. I felt like I was in a Jia Zhangke film, listening to a disembodied voice urging compliance with state policy. I imagined a modern-day Xiao Wu, the pickpocket anti-hero of Jia’s eponymous first feature, trying to eke out a living with the radio blasting overhead. In the movie, public loudspeakers blast anti-crime policies as Xiao Wu ambles through the city center. Thirty years later, in an American bagel shop, this movie still helps illuminate the disconnect between disembodied authority and the targeted individual’s experience.

With the liberalization and rapid expansion of the Chinese economy in the 1990s and early 2000s, the country underwent one of the largest urban migrations in human history—over 250 million people moved from rural areas into cities. Jia has always been interested in those left in the dust, turning his camera toward those displaced or disoriented by the country’s breakneck transformation. His characters drift through karaoke bars, mining towns, and construction zones. Time, for them, is in some way out of joint.

Many characters in his movies capitalize on reform policies, usually through a mix of shrewdness and fraud—like the gangster father in Mountains May Depart or the corrupt mine boss in A Touch of Sin. To Jia, this is par for the course in a market economy. Some exploit the grey zone opened up by privatisation policies to their benefit; others sink.

His movies often feel to me like microhistories, tracing the impact of vast socioeconomic changes on individuals. He weaves together documentary footage, archival recordings, and characters drawn from his own life, as though he were constructing an audiovisual museum of his own memories.

Jia’s focus on marginal cities and characters implicitly questions the extent of China’s rapid urbanization’s success, without explicitly condemning it. While many of his contemporaries were filming stories of disillusioned youth in dominant cities like Beijing and Shanghai, Jia has always kept his focus on people living in small towns known as “county-level” cities. With Deng Xiaoping’s pro-market reforms and official state narratives celebrating urban prosperity, Jia’s choice to set his films on the margins of China’s economic boom is radical and intentional.

In his films, Jia constantly returns to his hometown of Fenyang, a small industrial “county-level” city in northern China. Born into a working-class family there in 1970, Jia returned home in the ’90s while studying in Beijing and was struck by how drastically the place had changed. Entire streets were being torn down to make way for a new China.

“It was a time of immense pain,” he later recalled.

Jia’s relationship to Fenyang is captured in Walter Salles’ innovative documentary, Jia Zhangke, a Guy from Fenyang. This documentary takes seriously Jia’s own assertion that “a film is a memory” and locates Jia’s own memory within Fenyang. Salles follows Jia through the city as he revisits old haunts, talks to friends and family, and recounts the personal and political stories that shaped his life and work—from his father’s persecution during the Cultural Revolution to the joy his parents felt when Jia’s 2004 film The World was finally approved for domestic release.

Before 2004, Jia’s films were considered “underground”—produced without government approval. His early movies were mostly shown at film festivals outside of China, inaccessible to Chinese audiences except as bootleg discs smuggled in from Hong Kong. Even this “underground” label, Jia says, was not part of a larger political decision. Submitting his student debut Xiao Wu to foreign film festivals without realizing it needed official clearance, he was “suddenly labeled a so-called underground director,” he recalls, laughing.

Some may feel frustrated with the lack of clear political stances in Jia’s movies. But Jia’s mode has never been didactic. Just as museums teach us to look closely through thoughtful curation, Jia’s movies instruct us to pay attention to manifestations of power in the ordinary rhythms of daily life. Jia may not offer us solutions, but he gives us a way to start looking.

Stream A Touch of Sin and Mountains May Depart on Kino Film Collection.