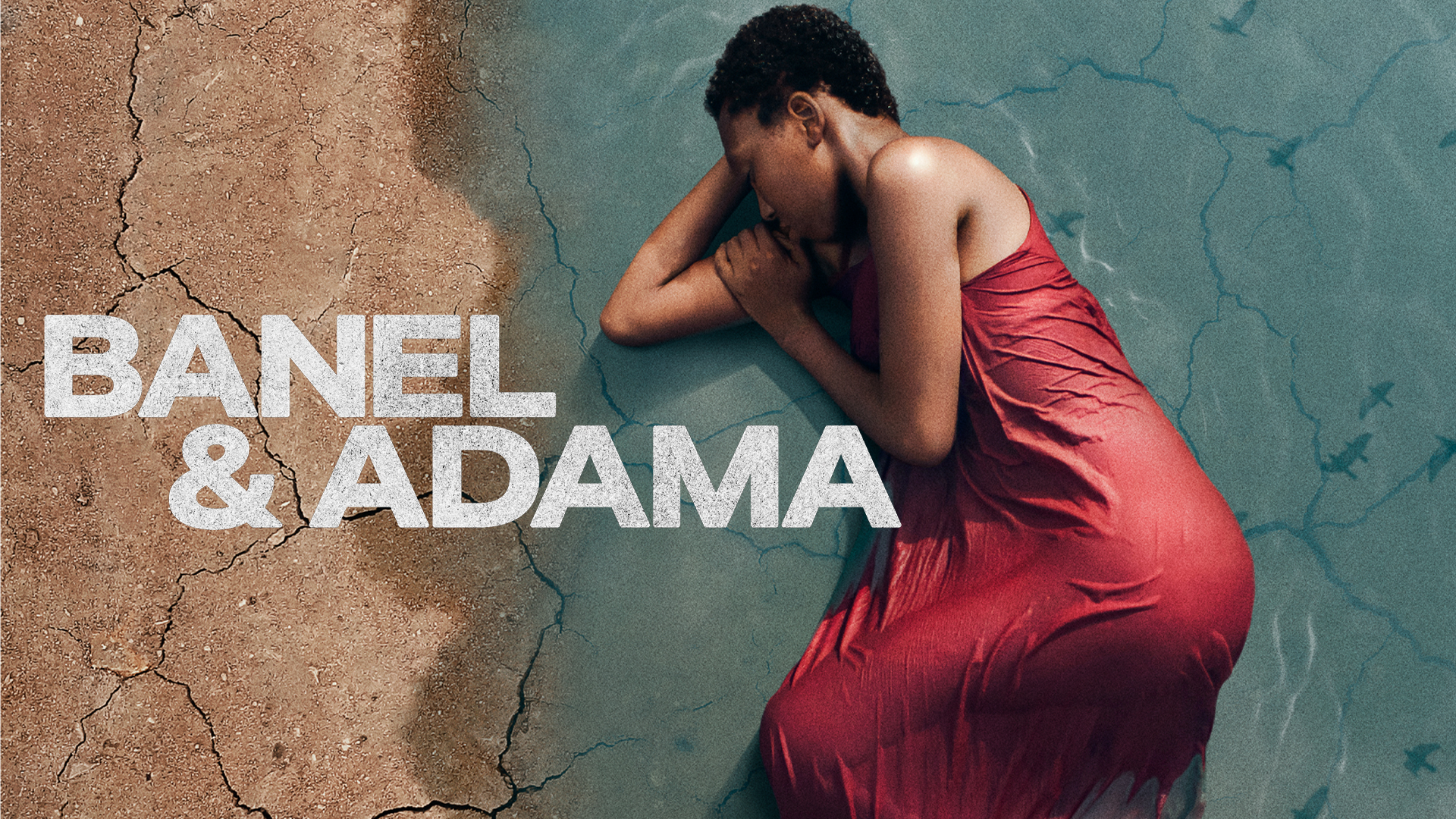

Watch: Ramata Toulaye-Sy’s Love Story ‘Banel & Adama’ Features the Female Anti-Hero Every Modern Woman Should Know

Be sure to watch our interview with Ramata Toulaye-Sy after the article.

“There is not one definition of being a woman,” Ramata Toulaye-Sy says matter-of-factly. “You can create your own definition.” Sy is referring to one half of the titular duo in her debut feature, Banel & Adama, and one of the most complex, multidimensional female characters in recent film history.

Kino Lorber had a chance to chat with the French-Senegalese filmmaker about her striking debut and what her goals were for creating a character like Banel. Though many critics have compared Sy’s Senegalese love story to Romeo and Juliet, she has a much more fitting Shakespearian heroine in mind. “[Banel is like] a Juliet who becomes a Lady Macbeth.”

As the audience, we inhabit the world through Banel’s point of view and we quickly delve inside her mind. We learn she’s both vulnerable and strong, filled with equal parts love and rage, and both driven by her own indomitable spirit yet unwaveringly devoted to her husband. Banel is unlike the other women in their rural northern Senegalese village. She wears her hair short, sits cross-legged and therefore “unladylike,” and has no interest in rearing children. “I didn’t want to create a kind, girly character,” Sy tells us. Banel would much rather break her back herding cattle in the field than do domestic chores, if only to spend the day with Adama.

Banel’s love for her husband fuels her dogged determination but is also perhaps the greatest source of her vulnerability. When she’s not writing their names down over and over on endless sheets of paper—a physical record of the mantra she repeats to herself—she and Adama dig tirelessly to unearth two houses on the outskirts of their village that have been buried by a sandstorm. Their shared goal is to live there, away from the pressures of village life. Or so it seems at first.

In the beginning, everything feels like a sun-drenched dream and Sy effectively unravels it thread by thread. The film opens with euphoric shots of married couple Banel and Adama frolicking through and laying in a verdant field of grass, lingering over each other’s features like they’re drinking each other in. They then take a refreshing dip in a glistening body of water. The choice to open with lush and aquatic imagery is not only a visually stunning one, but a clever exercise in contrast that only becomes clear later on as the film reveals the dark undercurrents beneath its shimmering love story.

But like with all love stories, Banel and Adama’s bond is tested. Initially, Adama refuses to be village chief, shirking a deep-seated tradition and choosing instead to live a quiet life with Banel. But as natural, and perhaps supernatural, forces take hold of the village, he begins to question his priorities. When a drought chokes the village dry and begins killing off the cattle and even villagers, the whole community, including Adama himself, begins to wonder whether it’s retribution from the gods for Adama’s rebellion. Love can be tested in many ways, but does it stand a chance against forces larger than the natural world?

Much of the film sees Banel descending into a slow-building emotional tailspin and some of the most memorable scenes involve her self-soothing the Banel way: putting her slingshot and deadly precision to use on small, unsuspecting creatures. It’s tinged with cruelty, sure, but viewers get the sense that this is actually the healthier alternative, a channel through which to tame her demons, demons that would otherwise run rampant in unimaginable ways. There are hints that she may have gone to extreme measures to be with Adama, whose brother was her first husband and who mysteriously met a tragic fate.

Is Banel’s fate also determined by her past deeds? Can love save her from her own darkness? Or was Banel never meant for a life of being saved from who she really is? These are some of the questions that are raised by the end of the film, which looks drastically different from the opening.

Sy and her cinematographer, Amine Berrada, deftly construct a visual journey filled with one sumptuous frame after another that gradually go from lush, glimmering, and full of promise to bone-dry, barren, but still somehow impossibly beautiful. “I wanted to compose paintings in my movie,” Sy says.” “I took inspiration from great painters like Amoaka Boafo, who is Ghanaian, Kerry James Marshall, who is African-American, but also Edvard Munch and Vincent van Gogh.”

Banel & Adama, which premiered at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, is a film that triumphs on so many levels—visually, technically, and emotionally—but its ultimate achievement is the character of Banel. Sy has created a truly incomparable female protagonist with more facets than people know what to do with. Sy admitted that while she was initially surprised by the audience’s ambivalent reaction to Banel, she ultimately sees it as mission accomplished. “In the end, I think it’s a good thing,” she says. “It’s not a problem if people don’t like Banel. I think the most important thing is that people understand her.”

Many critics have called Banel & Adama a parable. When asked what that lesson of the story is, Sy ponders for a second and responds, “I think the lesson of this story is be the woman you want to be.” Nobody embodies this lesson more than Banel. You may not like her, and you may even fear her, but you will not soon forget her.

Be sure to watch our entire conversation with Ramata Toulaye-Sy below and stream Banel & Adama on Kino Film Collection.