No Heroes, No Glory: Miklós Jancsó's Revolutionary War Cinema

War without heroes. History without grand narratives. Revolutions without champions. Miklós Jancsó, the late, great Hungarian director, destabilizes all genre conventions in his penetrating, pioneering features, many of which deal with Hungarian and Eastern European history.

One of Hungary’s most revered directors, Jancsó is finally getting the spotlight he deserves in the United States. Five of his most powerful films are now available to stream for the very first time on the Kino Film Collection. This long-overdue release brings Jancsó’s radical, visually innovative work to a new audience – decades after Béla Tarr called him “the greatest of all Hungarian filmmakers.”

Jancsó’s films are not typical war films. They are more like anti-epics – meditations on power, violence, and ideology that span over a century of Eastern European history. From the aftermath of Hungary’s 1848 uprising in The Round-Up to the civil war chaos of post-revolutionary Russia in The Red and the White, these works probe the moral core of war and revolution both visually and politically.

The Round-Up (1966)

The Puszta as Protagonist

Much of Jancsó’s cinema unfolds in the Hungarian puszta – a grassland farmed by various Eastern Hungarian ethnic groups for hundreds of years. The puszta is a key actor in Jancsó’s movies. It evokes a deeply interconnected Hungarian heritage as well as a sense of empty desolation. Jancsó’s films have sometimes been labeled nihilistic for their relentless critiques of ideology, violence, and power, the puszta spilling out like an empty stage (or page) of unwritten history.

Jancsó seamlessly moves between close-ups of individual pain and wide-angle shots of battle formations that have been compared to choreographed ballets. These visions of history make taking ideological sides as a viewer feel superfluous in the face of the reality of human suffering. Nowhere is Jancsó’s analysis of individual human suffering and history more piercing than in The Red and the White (1967), often called Jancsó’s masterpiece.

The Red and the White (1968)

The Red and the White: Revolutionizing Revolution

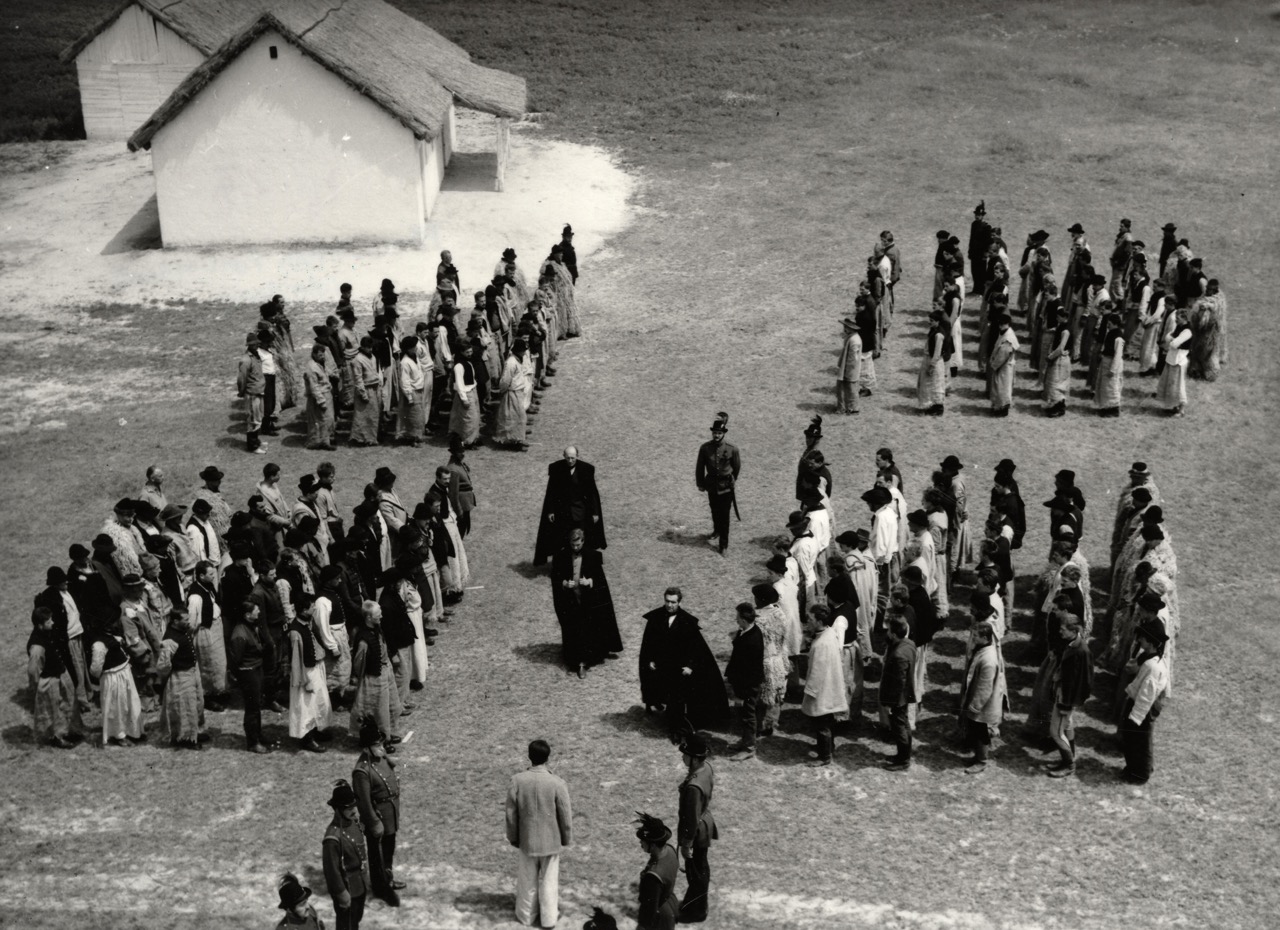

In The Red and the White, Jancsó focuses his camera on power struggles. This film was commissioned by the Soviet Union to mark the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution in Russia, in which the Bolsheviks seized power from the tsarists. The Soviet government intended it to be a cinematic celebration of the Bolshevik cause. Jancsó’s film, however, complicates this straightforward message.

Instead of during the October Revolution, he chooses to set the film during the Russian Civil War, two years after the Bolsheviks had already taken power. Instead of a celebration of the Bolshevik underdogs’ triumph, the film traces a complex historical period in which the Bolshevik “Reds” brutally held onto power against a coalition of anti-Bolshevik “Whites.” Millions died.

Jancsó leaves the film’s conclusion open-ended: what was the point of the war? Who benefited? Who had to die, and why? These questions are asked implicitly in the way Jancsó films the conflict. His camera moves from violent atrocity to violent atrocity. The brutal scenes take place almost exclusively off screen. Jancsó also rarely offers an explanation on the identity of the perpetrators. Sometimes, we hear someone call out “the Whites,” “the Reds,” “the Hungarians,” and can orient ourselves briefly in the narrative. Soon, however, we again lose track of the soldiers’ identities.

Jancsó is relentlessly realist. The film’s constant destabilization of justice and power, the fluctuations in cruelty as one side gains the upper hand, the pervasive sense of terror—it makes for a revolutionary, if sometimes exhausting, depiction of war, which defies all our preconceived notions of how a military film should look and make us feel. There are no heroes in this film. Even the most decisive characters are acting out of desperate fear. There is nowhere for the audience to rest in easy allegiances.

The anchor of this film is a group of female nurses working at a countryside hospital by the Volga River. They take in all the wounded, regardless of army affiliation. Much like the film’s audience, they do not seem to know or care whether these men are Whites or Reds. Upon discovering a group of seriously wounded soldiers, a nurse says “We have to write down the names of the dead for their families.” It is the singular moment of historical consciousness in a film filled with senseless death, the only glimpse of a potential future, a possible memory left behind from this war.

Jancsó does not allow us to rest here for long, however: the nurses are soon dispersed by an incoming horde of Bolshevik soldiers, who take the tsarist patients prisoner. Later on in the film, as the Whites return to the hospital to round up Red soldiers, they press a nurse under the threat of death to indicate the patients’ army affiliations. Her courageous answer – “We don’t have Reds or Whites here, only sick people” – voices the underlying moral stance of a movie that can sometimes feel like a nihilistic meditation on the pointlessness of violence.

The Red and the White (1968)

Radical Form, Radical Content

Jancsó was never interested in simplistic historical visions. He once said, “We must not accept historical events, but rather understand them.” That ethos runs through all his work. Whether it's a cinematic critique of military power or a poetic dissection of revolution, Jancsó’s destabilizing filmic language forces us to grapple with the gruesome morality of war.

Critic J. Hoberman put it best when he described Jancsó’s cinema as “a double vanguard, radical form in the service of radical content.” His long takes, wide-angle shots, and use of space – they all work together to destabilize not just the genre of the war film, but the way we learn and think about history. Especially in a present filled with devastating violence and deep ideological ruptures, Jancsó’s cinema offers a possibility for retaining our humanity while maintaining a clear moral vision.

Watch Now on Kino Film Collection

If you’re ready to experience a different kind of historical cinema – one that challenges its audience to rethink its relationship to war – don’t miss this rare chance to watch the work of Miklós Jancsó, available to stream for the first time in the U.S., exclusively on Kino Film Collection. All films restored in 4K from their original 35mm camera negatives by the National Film Institute Hungary – Film Archive.

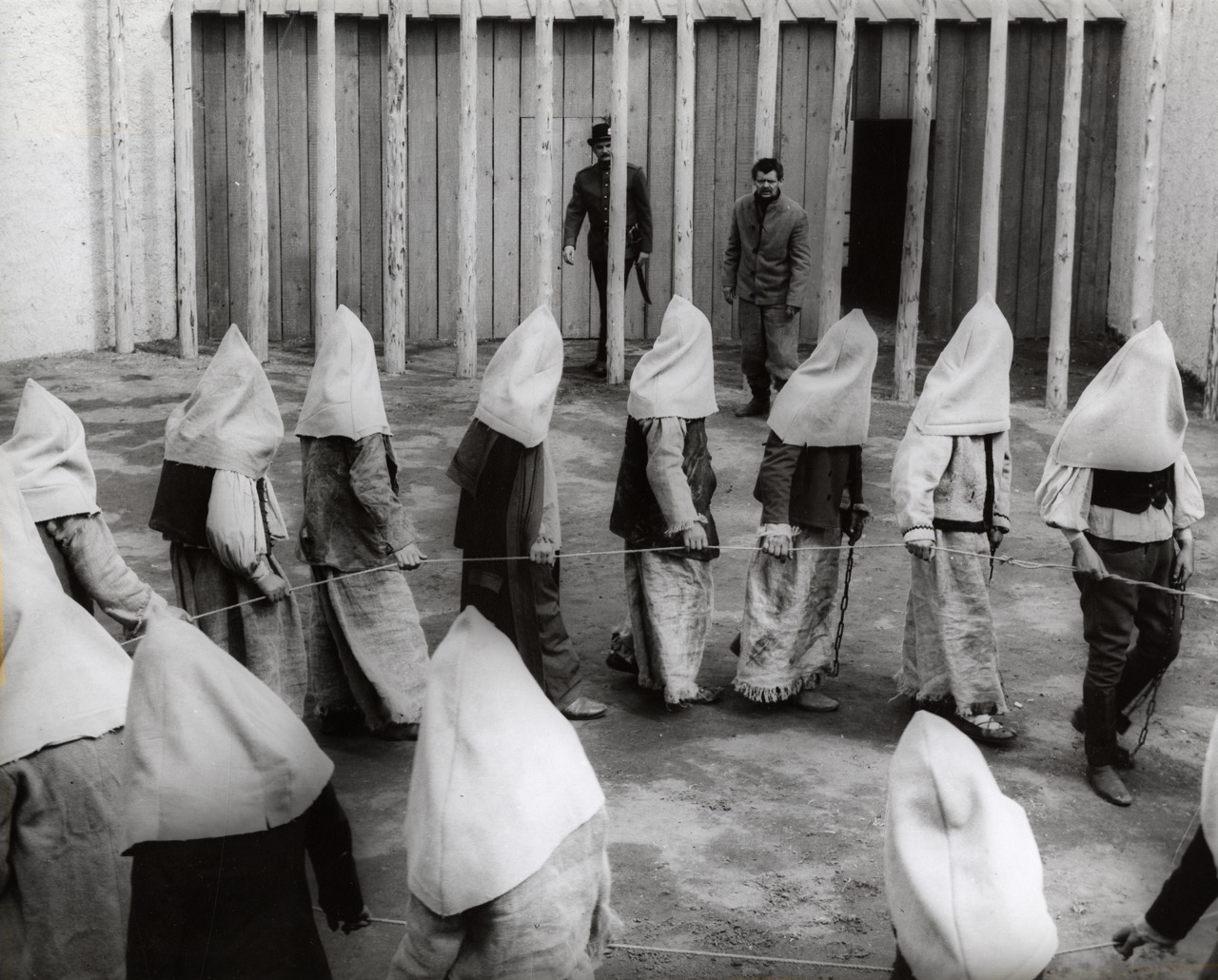

The Round-Up (1966)

Miklós Jancsó’s most renowned work depicts a prison camp in the aftermath of the 1848 Hungarian Revolution. After the Hapsburg monarchy succeeds in suppressing Lajos Kossuth's nationalist uprising, the army sets about arresting suspected guerillas, who are subject to torture and other mental trickery in an effort to extract information about highwayman Sándor Rózsa’s band of outlaws, still waging armed struggle against the Hapsburgs on the outside. Jancsó’s camera stays in constant, hypnotic motion, taking in the developing dynamics and antagonisms between the prisoners and their captors, meditating upon and exalting its characters’ resistance and perseverance in the face of brutal, authoritarian repression. A true classic of world cinema.

“I have never really been exposed to such a sensibility in the camera movements before (…) and the ending of The Round-Up is one of the greatest summations of a picture ever created.” –Martin Scorsese, Cannes Film Festival, 2010

The Red and the White (1968)

A haunting, powerful film about the absurdity and evil of war. Set in Central Russia during the Civil War of 1918, The Red and The White details the murderous entanglements between Russia's Red soldiers and the counter-revolutionary Whites in the hills along the Volga. The epic conflict moves with skillful speed from a deserted monastery to a riverbank hospital to a final, unforgettable hillside massacre. The Red and The White is a moving visual feast where every inch of the Cinemascope frame is used to magnificent effect. With his brilliant use of exceptionally long takes, vast and unchanging landscapes and Tamas Somlo's hypnotic black and white photography, Jancso gives the film the quality of a surreal nightmare. In the director's uncompromising world, people lose all sense of identity and become hopeless pawns in the ultimate game of chance.

Winter Wind (1969)

In the mid-1930s a group of Croatian anarchists led by the grim revolutionary ascetic Marko Lazar (played by the film’s French producer Jacques Charrier) escape a bungled ambush in Yugoslavia crossing the dense forests at that country's Northern border in an effort to seek refuge in Hungary. Winter Wind consists largely of twelve fluid long takes, some as long as ten minutes, and each a completely mapped-out sequence. Jancsó’s interest is more geometric than geopolitical, eschewing the big picture historic story for micro-social behavior. In a series of sweeping motions, effectively communicating the abstract conflict between the idealist anarchists and reality.

Red Psalm (1971)

Set on the Hungarian plains of the 1890s. When a group of farm workers go on a strike, demanding basic rights from a landowner, they are met with soldiers on horseback, facing harsh reprisals and the reality of revolt, oppression, morality and violence. Structured as a passion play. An awesome fusion of form with content, and politics with poetry. Stylized dance with collective choreography depicts the fight of those answering terror with violence. The film honors the agrarian Socialist movements of the end of the nineteenth century, while. conveying a historical philosophical critique of the Socialist ideas. Winner of the best director prize at Cannes in 1972, and widely considered to be the greatest Hungarian film of the 60s and 70s.

Electra, My Love (1974)